Making the invisible visible. The Networks of Dispossession map Turkish urban development processes

An interview with Yaşar Adnan Adanalı

The interview with Yaşar Adnan Adanalı focuses on the collective data-compiling and mapping project The Networks of Dispossession, which is dedicated to analyse the relations between urban development projects and the related concentration of capital and power in Turkey. As becomes clear in the course of the interview, the understanding of dispossession on which this mapping project is based is defined broadly. It includes the loss of natural resources, urban spaces, neighbourhoods, apartments and lives as a result of urban transformation processes.

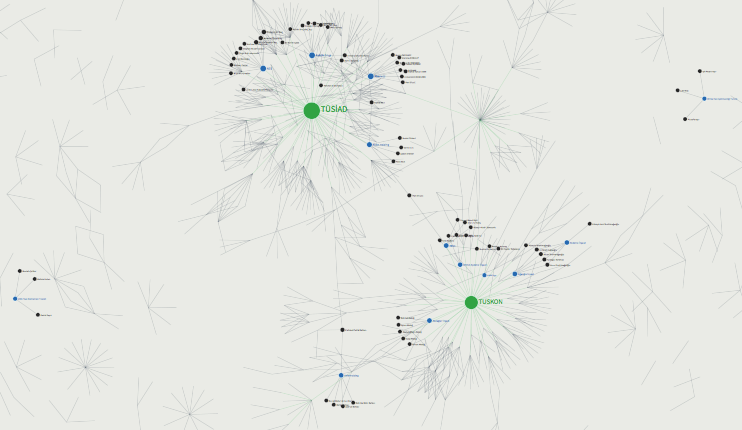

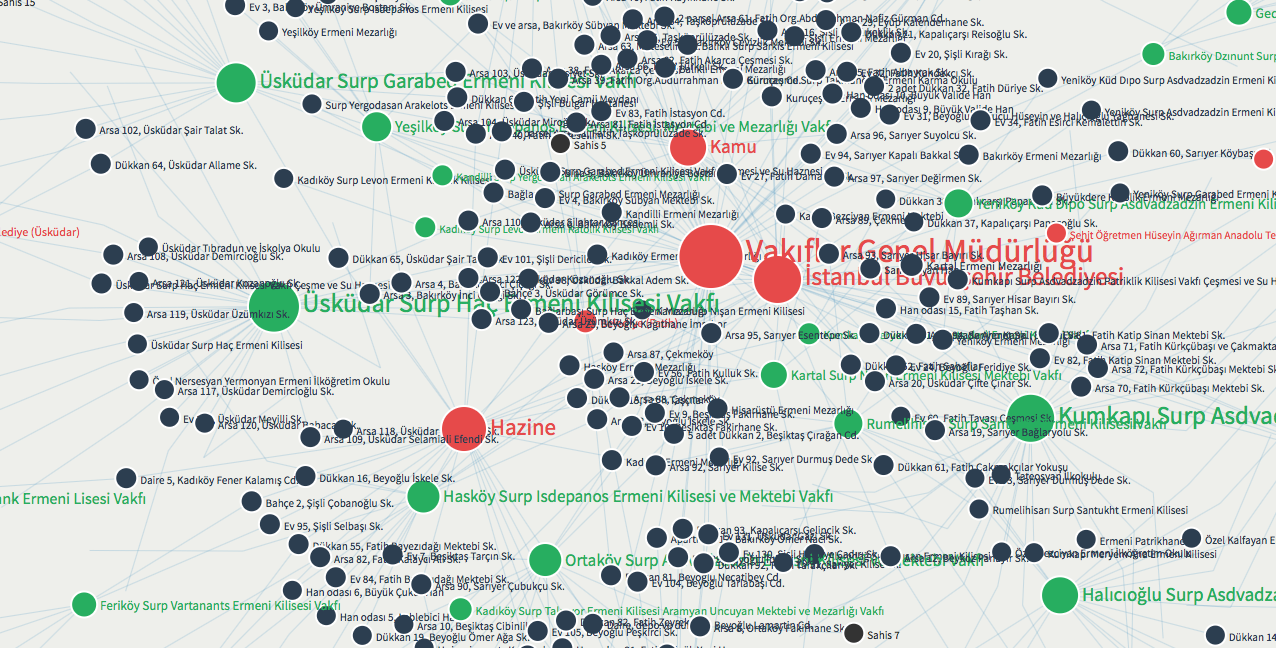

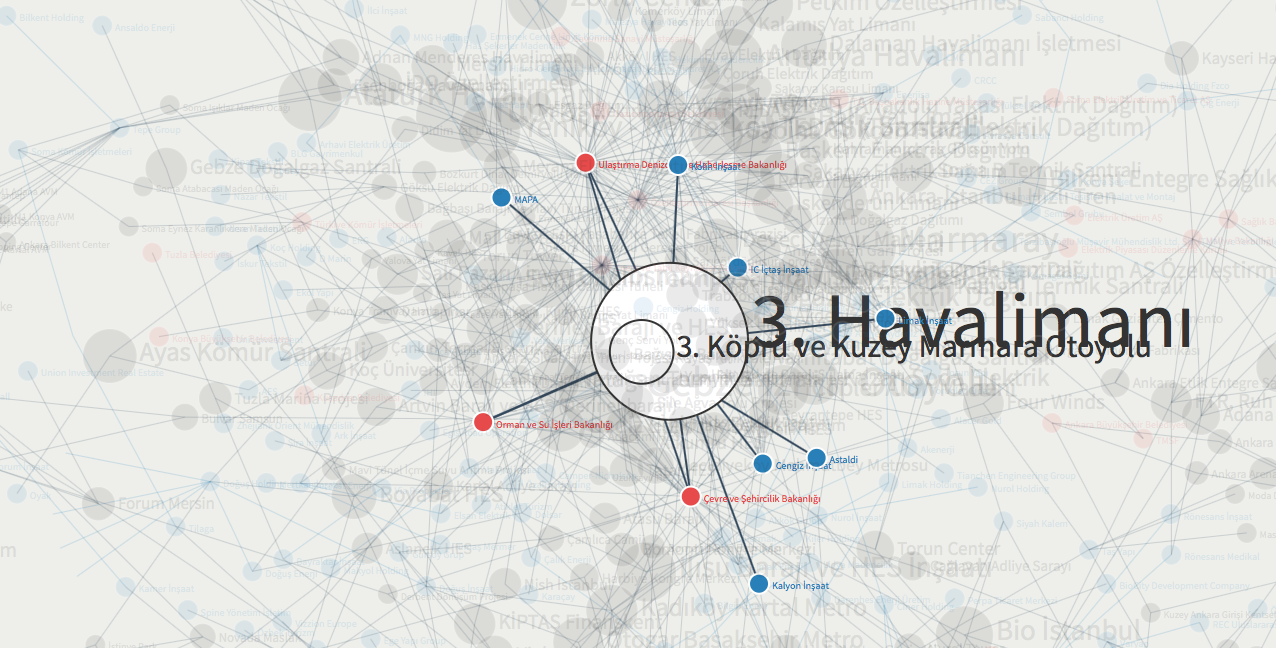

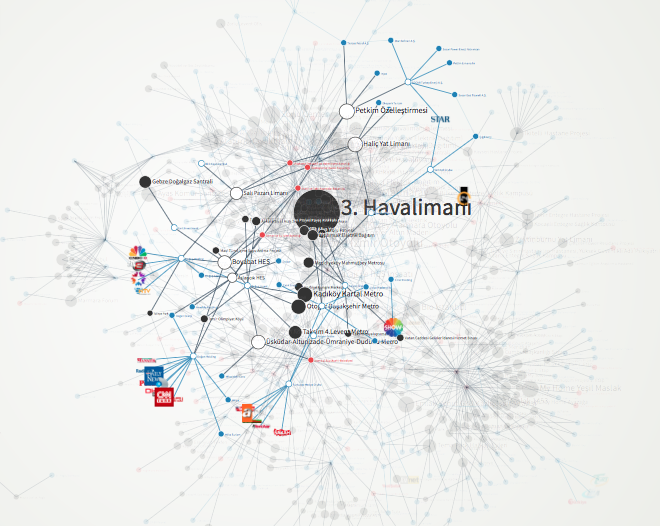

The Networks of Dispossession project includes three maps (link: mulksuzlestirme.org): the first map ‘Projects of Dispossession’ (see Figure 1) exposes partnerships of private corporations and governmental institutions in Turkey; the second map, ‘Partnerships of Dispossession’ (see Figure 2) reveals the close partnerships between different private developers, state actors and institutions and media companies; the third map ‘Dispossessed Minorities’ (see Figure 3 ) examines how properties of minorities, which were confiscated by governmental organizations, have been re-allocated over time.

Accountability and transparency are central to this mapping project. All the data used to generate the maps is referenced to publically available sources, such as the web pages of corporations, the Istanbul Chamber of Commerce database and Trade Registry Gazette, or to secondary resources such as newspaper articles.

Fig. 2 Partnerships of Dispossession (caption)

Fig. 3 Dispossessed Minorities (caption)

Nina Gribat (NG): How did you get the idea to map the Networks of Dispossession?

Yaşar Adnan Adanalı (YAA): In the beginning of the Gezi uprising, a group of friends – Burak Arıkan, an artist, me, a researcher and blogger, a few journalists, lawyers and employees in investment companies started talking about a few urban transformation questions that we were interested in and already working on: Who are the actors of urban transformation? Who is developing the large urban transformation projects that are creating all the discontent among the broader population? What sort of public-private partnership allows these projects to happen? And why do they appear so inevitable? We decided to organize a workshop on these questions at Gezi Park. Our discussion started from the Gezi Park Project itself (the plans of the government to reconstruct the Taksim Barracks instead of the park, which were the initial trigger for the Gezi protests). Then, we related the Gezi project to other urban development projects. After the meeting in the park, we started organizing online. First, we defined the general framework of our enquiry then, all we had to do was to generate a database. We used a spreadsheet and started collecting information about different urban transformation projects and their respective developers. Then, we started looking at other projects of these developers.

NG: What exactly can we see on the Projects of Dispossession map?

YAA: There are urban transformation projects, so-called mega projects – ‘mega’ in terms of their huge public investment, like the 22 billion Euro airport (see Figure 4); or in terms of their huge impact on the city, like changing a neighbourhood into a shopping mall; or ‘mega’ in terms of the huge impact on the ecology, like building a huge highway in the northern forest area of Istanbul; or in terms of the huge cultural and symbolic significance like building the biggest mosque on top of Çamlıca hill, which will be visible from all around the city. The monetary value of this mosque will be one percent of the airport project, but in terms of its symbolic impact the mosque might be more important. The more ‘mega’ these projects are, the more contradictions and conflicts they tend to create.

Since the current AKP government came to power in 2002, economic growth in Turkey has been heavily dependent upon the development of the construction sector. Turkey is experiencing an urban transformation at a massive scale. The expected number of housing units in Turkey to be demolished and redeveloped is around 7 million, a substantial part of which is located in Istanbul. In many instances, whole neighbourhoods are being designated as renewal sites, demolished and redeveloped as gated communities or shopping malls. Much of the urban renewal process in Turkey can be associated with a lack of participation and a failure to put the demands of the people who live in urban transformation areas at the centre. The renewal process in Turkey is almost a text-book case of dispossessing the urban middle- to lower middle classes through renewal projects that are planned to make profit.

NG: Which urban transformation projects did you map and where are they located?

YAA: We mapped urban regeneration projects at the outskirts of Istanbul as well as in the city centre. We also mapped small-scale hydro-electric dam projects in rural areas, which are supposed to be a sustainable renewable energy source but which are rather peculiar development projects in the northern part of Turkey. You see them all around. They are an extremely interesting case of dispossession because they are heavily promoted by the government as part of environmental policy. These small-scale hydro-electric projects go all the way up a river – even if it is small rivers. They divert the water from the riverbeds and feed it into tubes that go zigzag down the mountain through various energy turbines. While the water generates electricity various times, the river is deprived of water. Only survival water is still flowing so that nature also gets what is considered ‘its fair share’. We realized that because there were hundreds of such projects, all the special ecological areas, in which these hydro-electric projects are located have been radically transformed in the last few years. Villagers who live there started loosing their water source; the vegetation and the animals were being deprived of water. The companies that develop and operate hydro-electrical projects also get the right to sell the water that they use. So in the end they can even bottle the water and sell it on the market! They haven’t start doing that yet, but they could. In addition, the companies can also trade the carbon on an international market because the energy production is supposed to be renewable. This is one of the most problematic forms of supposedly ‘sustainable’ development we have and in these villages one of the most active resistance movements is forming.

We didn’t choose the combination of mega projects – incl. urban renewal projects, hydro-electric projects, and mining projects from the beginning – even though they are all projects that have direct impact on the population and the environment and on our urban and rural commons. We didn’t first categorise and then search for the projects. We started from the Gezi Park project and looked for other projects that were carried out by the same developers – and that’s how the combination of projects I just talked about were the projects that came to our attention. We could have also done it the other way around starting with an extensive list of projects of dispossession, but instead, we started with the impeding dispossession of a public park through a mega construction project, the reconstruction of the Taksim Barracks. From there, the map just spread to include all these various elements.

NG: How did you come to include the connection to the media?

YAA: During the Gezi Park uprising one critical issue was the status of the media. It was very difficult in Turkish media to really get any unbiased news about what is happening. One very striking example of this is that CNN Turk was showing a penguin documentary during the heyday of Gezi, while for the first time in Turkish history something extraordinary at this scale was happening! They didn’t have to take a position for or against what was happening but they could have at least done what a news channel normally does and report what was going on. It was such a unique opportunity for any news channel, for any newspaper to follow, write and report about Millions of people were on the street! News channels normally love these kinds of events, but on CNN Turk, it remained very quiet. Other news channels like NTV also showed almost nothing about Gezi. Eventually people went to their headquarters and protested in front of them. The demands of the protesters were simple: until you make us visible in your channel we will not leave. In a live show, the TV journalists, then, came out of their offices and said: “In front of our offices Gezi protesters are protesting because we are not producing any news about the Gezi Park protest”. In a way people reclaimed their right to receive news by occupying the news channel. So, during Gezi, the media was a huge problem, so we decided to also look at the media ownership in the Networks of Dispossession. We wanted to know if the companies that built the urban renewal projects also owned major news channels.

We realized that the investors or urban transformation projects own almost all of the major news channels (see Figure 5). For instance, one of the urban regeneration projects, Tarlabaşı regeneration project was done by the company that also owns one of the biggest media corporations, which is run by the son in law of the Prime Minister Erdoğan (now the President). When you put all the media together and you see how it is part of the Networks of Dispossession then you see – without putting extra commentary to it – that there is a real crisis of democracy! That is why I keep on saying that there is an urban crisis in Turkey, which goes hand in hand with a democratic crisis.

NG: In addition to this you also mapped the deaths that occurred in connection to the urban renewal projects. Can you talk a bit about this?

YAA: We also wanted to include the labour murders because of the argument that the very appetite for development happens not only at the expense of our public spaces and our urban and rural commons, but it was also dispossessing the workers from their right to live. We wanted to make this argument visible, so we highlighted those projects where, during the construction, workers lost their lives because of poor or no safety regulations.

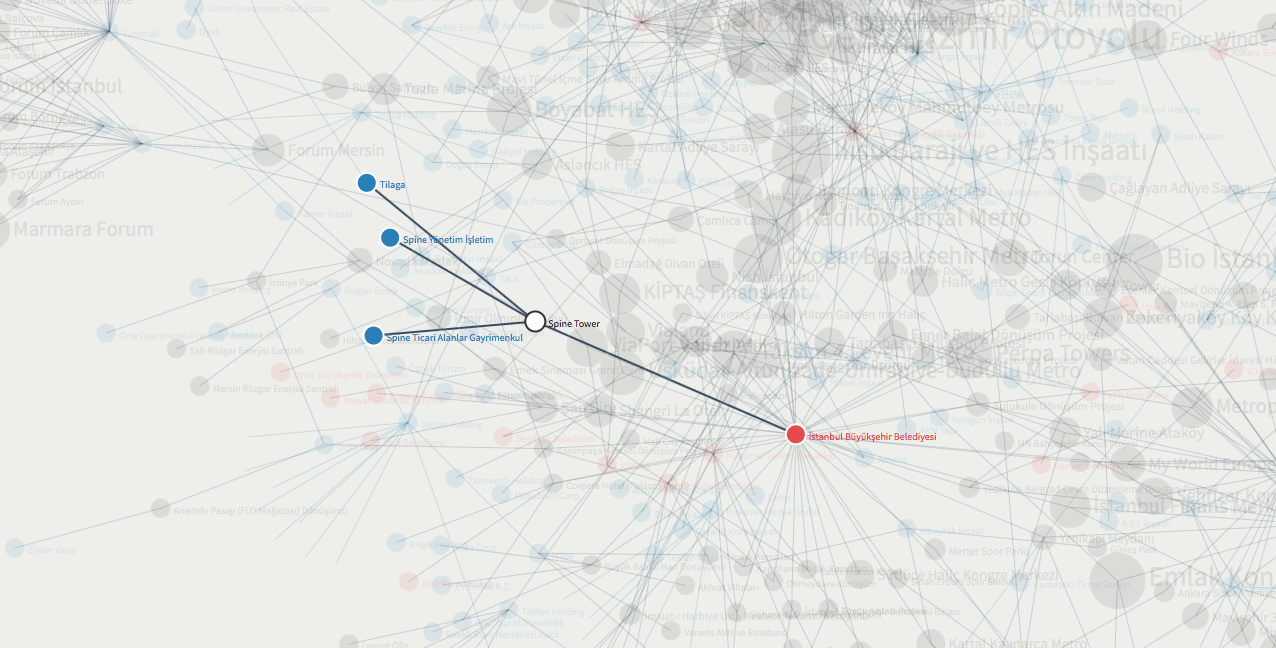

How relevant this was became obvious during the Soma mining massacre in May 2014. The mining sector, which – in Turkey – follows very much a public-private-partnership model exploits the workers. There are poor working conditions and no governmental safety regulations. The mining company invested the surplus value that they extracted from their workers in the mines into projects in the centre of Istanbul, building the highest skyscraper. They even claimed that this skyscraper would be the “safest” skyscraper in Turkey because based on being a mining company they could use the best cement. But because they were not providing the best of everything to the workers in their mines, 300 of their workers lost their lives in the biggest mining accident in Europe for at least a decade and in Turkey by far. You see – this was very much connected – a real estate development project in the central business district of Istanbul, which was – by the way – also a project of dispossession because it had a very controversial building permit exceeding the existing building limits. This project was made possible by the connection to a small mining town, where the company basically killed more than 300 people (see Figure 6). All this was only possible because the private mining company could get into partnership with the Turkish state. The state provided a guarantee to the company to buy as much coal extracted as possible from that mine, which paved the way to the race to the bottom for the workers.

Fig. 6 The Spine Tower was built by the mining company, in whose mine 300 workers lost their lives in an accident (caption)

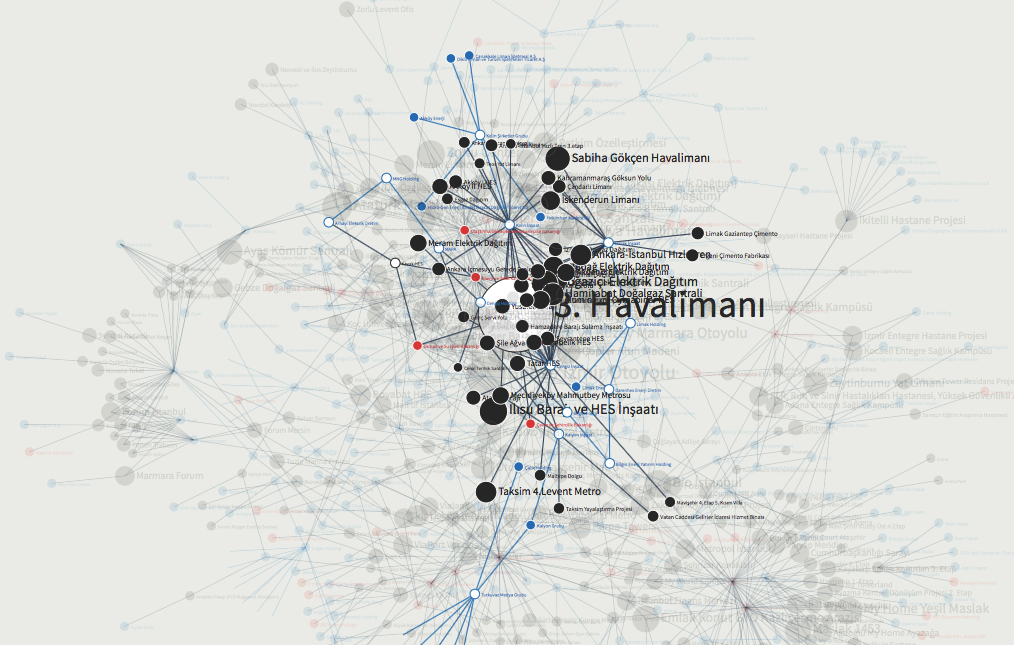

Fig. 7 Close linkages between large construction companies and public actors (caption)

NG: Now we have the developers, we have the projects, we have the media and the workers who lost their lives. You have started to hint a bit at the involvement of the state. Can you go into a bit more detail regarding the role of the Turkish state?

YAA: The urban transformation projects were not just carried out by developers. These projects were developed in public-private-partnerships, so we also looked at the public stakeholders. For example, the Mass Housing Administration Under the Prime Ministry (called TOKI in Turkish) develops numerous real estate projects, mainly vertical gated communities for middle or upper middle classes at prime locations and so-called ‘social housing projects’ for middle to low income groups at the periphery of the cities in partnership with private developers. These projects are mostly located on public land and carried out according to a profit sharing model. Other public authorities such as certain ministries and municipalities are also very visible and prominent in our map because they are actually working as the connecting points. You can, for instance see a cluster of mega infrastructural projects that are developed by certain developers who are in very close relation to the very top of the government (see Figure 7). And the government actors are again connected to a group of large construction companies. The guys who develop the bigger cake, through these partnerships also have connections to the guys who are developing the smaller cakes. This was the map of the Projects of Dispossession.

The hashtag we were using a lot during the promotion of the Maps of Dispossession project on social media was #KentselDönüşümLobisi (“urban transformation lobby”) – lobby referring to the fact that during the Gezi uprisings the Prime Minister and his advisors were keen on looking for a ‘lobby’ behind the protesters, such as the ‘German airport lobby’ or the US interest lobby. The Prime Minister and his advisors made up all these mad arguments, which also shows that they had no intention of understanding what the people were demanding in Gezi. Our hashtag was a way of expressing that the links they were building in this Network of Dispossession was the real lobby – an urban transformation lobby.

NG: Is the Projects of Dispossession map organized spatially based on where the projects are located?

YAA: No, it is not organized spatially at all. In clicking on the projects you can get information about their spatial location. The network map is about making visible the public-private partnerships on which the projects are based and which also interlink them amongst each other. Through this visibility we wanted to open a public discussion. We hoped that people would start to question the lack of transparency in the urban transformation processes in Turkey. Our basic argument was that through all these urban and rural transformation projects we were seeing a process of concentration of power in terms of decision making and a concentration in terms of capital. The following examples of Gezi Park or of the Tarlabaşı area show this: while we were being dispossessed of our park and while thousands of people were dispossessed of their neighbourhood, other people were making a lot of money; or EMEK Cinema: while the people of Istanbul were dispossessed of their heritage building, other people were making money. This dispossession process was made possible by and also paved the way for the concentration of capital and power. It was a process going away from democratization and that is why we were arguing that we are in a crisis – a crisis that became very much exposed during the Gezi Park uprising. It was the accumulation of all the urban ecological and democratic crises in Turkey and our maps make the connections between these seemingly distinct crises very visible.

NG: In addition to the Projects map you also produced other maps, can you tell me a bit more about these?

YAA: Yes, there are different maps because this network mapping methodology allows us to pull out different aspects. The second map focuses on Partnerships of Dispossession: we started researching more about the companies focusing in particular on the board members. We were going through the trade journals, public data, until we uncovered how all individuals are interlinked. This is important because in many cases one individual is sitting on many different boards. These development companies belong to different holding corporations but in the end they are connected very closely through these individuals.

NG: So the individuals sit in different positions and thus you know that the network is closely knit…

YAA: Yes, exactly, the network is closely knit and this has wider implications because all these companies are working in the same sector. Theoretically they are supposed to compete with each other. Mapping how closely these companies are linked, you know that there is almost a cartel in the construction sector in Turkey. The second map shows this. And the third map on Dispossessed Minorities is closely related to the decision of exhibiting the maps in a particular location. The Networks of Dispossession were exhibited at the Istanbul Biennale in September 2013 and the Biennale location that we were going to exhibit in was an old Greek school. This school was taken away from the Greek community by the Turkish state many years ago like a lot of other properties from other non-Muslim communities. These buildings have either been used by the Turkish state or they have been privatized. So this was another sort of dispossession and we thought it was necessary to add a historical reading to our mapping of contemporary dispossession processes to emphasise that these state-capital partnerships operating today are very much informed by historical processes. The map we showed was mainly based on data we gathered from the Armenian foundations because they had better records than, for instance, the Greek foundations.

In the Dispossessed Minorities map you can see a particular property, the community that used to own it and the public institution or private actor who owns it now. A couple of years ago a new law was passed, which allows some of the communities to claim their properties back. So the history of dispossession in Turkey is somehow acknowledged. Of course this is also very problematic because now the number of community members has diminished and others have disappeared and some properties have already been demolished. But still, the reclaiming process has opened a path and through this map we wanted to make our statement in a very symbolic place.

NG: Who contributed to the database on which your mapping project is based? How many people were you and where did you come from?

YAA: In the inner circle there were eight to ten people who came together and shared their research from time to time. Then it spread and people were mainly working from their desks. We received some contributions from a broader circle of maybe up to 20 people. After the maps came to a certain level we had a few workshops to get feedback. This enlarged circle also contributed. The people involved come from very different disciplines we have urbanists, we have lawyers, we have investors, we have artists, we have activists, we have journalists. It is our common interest that brings us together from various places. People could put in their own specialisation and their own knowledge. The work itself didn’t require any specific skills or knowledge – just doing research was enough.

NG: How did the translation work from the database you collected into the map?

YAA: Basically, if you look at the map, it is a very simple visualization. As an infrastructure we use Graphcommons (graphcommons.org), which was developed by our colleague Burak Arıkan. It is an open source mapping platform that allows you to build these kind of networks. There was a host of the visualizing, so we didn’t have to worry about it. And the rest… everyone stepped in with their own contributions. We had journalists in the team who could take the products (the maps) and make news about them. They were anonymous members of our team, concealing their involvement, but they helped to spread the news. Then we had people working in investment firms. They knew much about the urban transformation projects. You cannot call it “insider” information that these friends provided, because everything was public information. For some information you would have had to look for it more intensely. For someone who is already informed access was much easier. Me, I was writing and I was willing to publicly promote or reflect upon the maps. So at some point I was in various news channels to promote the maps. All these elements came together eventually and it worked…

NG: You basically publicized the maps, and how was it then taken up? What happened then?

YAA: First of all, Istanbul Biennale helped to make the Networks of Dispossession more public… They asked us to participate. I was communicating with the Biennale team, not for the maps, but for various other things. Our artist friend Burak was also communicating with them. Once they saw the potential of the work, they wanted to provide the platform. Then we discussed in the group whether it was a good decision to go to the Biennale because it was quite a problematic mega event in itself. We had all our freedom, we were already doing what we were doing. We didn’t get any personal benefit from being part of the Biennale, like money or anything else. We were sure about the content and the leverage about this work. And we thought, when you can reach out to many people on such a platform, you can have a big impact. The Biennale just became a podium for what we were doing anyways. We didn’t produce something for the sake of being part of the Biennale. That made a big difference and it is why we decided to do it. Through Biennale we received a lot of positive comments. Even the Financial Times wrote about the maps, saying that it is a groundbreaking work. That was super powerful. The Financial Times are supposed to be on the side of the capital, but they still acknowledged our impact. The national newspapers were very much promoting our maps. This allowed us to talk to various communities, which was also supported by the fact that the entry to the Biennale was free this time. The map was first considered as a work of art, then as a work of research, a work of advocacy, then as a piece of journalism, so it could talk to various communities: the artist community, the media community, the journalist community, the citizens, activists, politicians. There were these members of the opposition who were involved in investigating corruption allegations in relation to the projects we had mapped. They were very much interested in the maps and in supporting our work. They were even sending some extra information and contributed to disseminating the maps. So partially this was due to having such a great visibility based on the Biennale contribution. But I still believe that if we hadn’t joined Biennale, we would have eventually also reached out to many people because history was just making the maps very visible and important.

NG: Can you reflect a bit about the overall impact of the maps?

YAA: As I said, our work talked to various communities. In addition, it was a message to some of the developers – who have or have not been mapped yet. It was a message saying “you can be mapped”. It was also a message to the architects of these projects who were also very much in the spotlight. I realized in various events where architects were talking that they were actually also sharing our maps. Architects active in the market were referring to the maps and warning their professional network “you can be there, watch out”.

With this project we wanted to have an impact on the public discussion and open a new public sphere about the way in which these urban transformation projects have been discussed. It was very important for us that the maps are based on data, connection and visibility, so that everyone knows you go beyond speculation and this very simple rhetorical level. We could actually base our argument on data. In relation to the corruption investigations on 17 December 2013 most of the guys in our map were taken into custody, which meant that we highlighted something that went wrong. At that time, the public discussion centered around these issues and we made our modest contribution for those people who were interested in the network and the system behind it. Our maps allowed us to argue that these corruption allegations are not only about taking money from one’s pocket and putting it into another one’s pocket, but that this was actually related to a bigger urban transformation process in which the broader public was being dispossessed: from their houses, from their forests, from their water.

NG: How come that you did not map the extended effects of dispossession itself? Including statements like: 300 families lose their houses…

YAA: We included links to the sources of information on which our map was based and if you want to click on them, you can read about some of the effects. We didn’t want to be so descriptive and say “because of this project…”. We didn’t feel the need to do that. We only included the labour murderers that lost their lives because we felt it was very important to make that statement. We could have mapped the various impacts such as eviction or gentrification or ecological damage, but we didn’t at that stage.

NG: What you are saying about the revelation oft he corruption cases sounds quite optimistic – are there signs that things will improve?

YAA: Well, that is not entirely true... A few times very big mainstream TV channels wanted to invite us, but they always stepped back. So I was wondering if they were held back or if they self-censored. It is important to understand that it is not possible to get into any kind of constructive public dialogue, especially since Gezi, since all this crisis management from the government’s side was to put up these binary oppositions and hostilities make it appear as if what Turkey is going through is kind of a cold war.

NG: Is this your thesis or is that the thesis of the government?

YAA: I am interpreting the government’s reactions as an internal cold war. They also openly call the protesters ‘looters’: “looters are in coalition with international deep (underground) forces”; or they bring forth these lobby arguments: “The bankers, the finances, the countries of the west are provoking these so-called citizens”. These conspiracy theories were very much propagated in Turkey.

N: And your decision to react to this was to put something out that is not based on speculations, but on facts.

YAA: Yes, we wanted to take the discussion away from this realm of heavy rhetoric and unsubstantiated claims and focus on the realm of data and facts. For instance, there was one incident on the news and suddenly the government started saying that naked protesters peed on and beat up a pious head-scarved pregnant woman with a baby – in the middle of the day. This was one of the fantasy images that they were trying to create by saying that Gezi is based on a lynch mob. In the past, just a few months ago you would have considered these people as quite considered journalists and politicians, even though they were from the other side. These were mechanisms that were used to break down society in the middle. When we actually saw the videos, we realized that there was almost no contact between the woman passing by and the people – there was not even a big protest! All these huge lies: the government’s campaign was built on something that even in the first instance sounded very impossible or crazy. How could this have happened? After you see the videos you realize that something else was happening! We were in this very mad situation in which it was very difficult to reach people – even through facts.

NG: I would like to talk a little bit about the point of interpretation in the map. Understanding them as ‘pure facts’ is misleading – the selection of which facts you put out is an interpretation itself. Your map somehow makes certain connections more prominent then others – how does this mechanism work? The visual representation in terms of the data…

YAA: When we published the map, there was much talk about why we didn’t include this or that project – as if we were trying to hide certain projects or certain actors. The Networks of Dispossession are a project in progress, it can grow. We still collect data and the second version had already become double in size.

In terms of how the representation works: we included the sums of investment of the projects – how much space they occupy in the Turkish economy according to the project budget. We used different sizes of circles to represent the projects in terms of their monetary value. You could see the small and the big fishes. You could come up with different visual readings. There can be relatively small projects, but many of them, and in the end they were developed by the same actor – so in the end what does that mean? Or you could follow certain paths and this also gives you some interesting readings: One particular project could be connected to another, that we would probably not think about if we did not see the connection. The simple reading is about how big the projects are and then how they are connected and where the connections take you… When you include the media and the links with the public authorities it becomes a bit more complex.

It wouldn’t be fair to call it “pure data” and nothing else. Of course there is an interpretation, but it is still open to other and further interpretations. Zooming in and out is one way of looking at the map. The intensity and lack of connections are another way. The relationships between public and private actors are another. And the way in which some actors act as transition nodes also opens up new interpretations.

NG: Do you reckon that social media made a difference in terms of the impacts of your maps?

YAA: Yes, social media, and normal media, and our willingness to be visible on TV, radio and the news – all this helped the maps to gain visibility. And of course, you are offering a particular reading when sharing it, at least you make a comment while you are sharing it. You direct people in ways of reading the maps. When there is an incidence related to a particular project or by a particular actor, you can zoom in and point that out on the map. And right away you offer a context of dispossession on which that particularity gains a more systemic meaning.

NG: Yaşar, thanks a lot for this exciting interview.

Interview, transcription, editing and translation: Nina Gribat.

Beteiligte

Yaşar Adnan Adanalı is an urban researcher, activist and blogger. He currently works on projects that foster spatial justice and enhance urban democracy.

yasaradanali@gmail.com

Nina Gribat is an urban and planning researcher. She is currently working on international comparative research projects that focus on urban development conflicts, shrinking cities and the university reforms and protests around 1968.

nina.gribat@tu-berlin.de